Politics and prefabs

“People have got the idea that it (prefabrication) means jerry building, tumbledown shacks, caravans, shoddy work, ribbon development, draughts and leaks and everything that’s bad in building. The Government itself seems to hold the confused opinion that prefabricated means temporary”. Picture Post, 1945

Here is a quote from The Times, 12 November 2016, following an announcement that the UK government was looking into the potential of prefabrication.

Pride in prefabs can help solve housing crisis

Vive la difference!

Reading transcripts from House of Commons debates about Housing, the Temporary Housing Programme and Emergency Factory Made Homes is like reading a very lengthy version of the Three Bears. Prefabs were, according to MPs: too small, too big, too good, not good enough, too expensive, too wasteful, too many doors, took up too much space; would put people out of work, might become permanent etc etc etc. You may come to the conclusion that when so little is agreed, much less is carried out. So let’s start by quoting the Minister of Works in December 1944.

I would like to turn to the question of temporary houses. There has been a good deal of criticism in this Debate, and also in the Press just recently, about the whole of the Government’s temporary housing policy. It seems that it is still not fully understood why we have adopted this course. It all boils down to one thing, and that is the shortage of building labour. This has been the deciding factor coupled with the fact that other types of labour in the engineering industries will, at the end of the war with Germany, become available in limited quantities. It was the shortage of building labour which led to the adoption of the temporary factory-made dwelling. The strength of the building industry before the war was 1,000,000. It is now down to about one-third of that strength and, of course, a very large part of it is not available for work of this kind.

Thus the primary objective of my Noble Friend Lord Portal, whose inspiration and assiduous personal attention played so big a part, was to provide a house whose construction would make the absolute minimum demand on building labour. The other consideration was to try and bring the great engineering industries into the housing programme, and to let them play their part in meeting the housing shortage. It was not possible to convert the men and women in munition factories into plumbers and bricklayers. The only way round the difficulty was to re-design the houses so as to make them suitable for the labour available to produce them. By the adoption of these novel methods, which represented nothing less than a revolution in British building design, we are going to be able, with the same force of building labour, to produce nearly three times as many houses as would otherwise be possible. Jigs and tools needed for the manufacture of this pressed-steel house and the internal fitments are now in course of preparation. I must, however, make it quite clear—and I would like there to be no misunderstanding about this—that the actual production cannot be proceeded with until the necessary labour and manufacturing capacity are released at the end of the war in Europe. (1)

As early as 1941, local authorities met to propose a sectional bungalow that could be erected in five days and stored at key points across the country, to be assembled following air raids (2). The proposal was not taken further and emergency accommodation was requisitioned in the form of Seco Huts and corrugated asbestos cement Nissen Huts, both of which had been used as temporary airfield accommodation.

Other factors influenced the Temporary Housing Programme and Emergency Factory Made Homes, apart from the acute shortage of labour and destruction/damage to housing stock during the Blitz and subsequently:

- The willingness of manufacturers to utilise their factories to produce housing

- A shortage of raw materials, particularly timber, which led to furniture rationing and indirectly to the provision of fitted cupboards in the prefabs

- The unfinished business of clearing slums and building new homes in the inter-war period

- Convincing the population that it wasn’t just another broken promise or shoddy solution

The government and the manufacturers didn’t wait until the end of the war to begin production and erecting the factory made homes. £150,000,000 was authorised after the act was passed in 1944, and the first prefabs were up by spring 1945. The pressed steel ‘Portal House’ (shown here in the film ‘Home of the Future’) never went into production because the factories could not be released from wartime activities until after the war ended. This led to less highly prefabricated models being adopted, with the exception of the aluminium B2 bungalow which was cast in four sections.

This was the first time central government had taken control of public housing. To understand how the temporary housing programme centralised the supply of public housing we have to go back to the Municipal Corporations Acts of the 19th century; first the reformation of local government and the introduction of local elections, the second the acquisition of land and buildings. The municipal corporations built their own housing and facilities to meet local need through a combination of local taxes, bonds and loans. After WW1, during which new housing had ground to a halt, the the Addison ‘Homes for Heroes’ Act of 1919 provided grants and subsidies to clear slums and build new homes. Over time these grants and subsidies waxed and waned according to whichever political party was in power and the economic circumstances of the period.

After the passing of the Act in 1944, local authorities were tasked with applying for, finding and acquiring sites for the temporary homes, organising and installing the utilities and infrastructure. Once this was complete the sites were handed over to the Ministry of Works. Local authorities were responsible for allocating tenants for the prefabs once they had been delivered and erected. Many local authorities had developed plans for particular sites before the onset of WW2; these had to be shelved in preference to the prefabs!

Costs escalated as sites had to be cleared of rubble, uneven sites had to be levelled or compensated for, smaller manufacturers were engaged to produce some of the modified components and fixtures and fittings; breakages and damages, underestimates of labour and subsistence, improvements in infrastructure and administration costs all had to be taken into account. This added an average of £268 to the cost of each prefab. The programme envisaged that groups of 200 prefabs would be sited on the outskirts of towns and cities, but in the event London averaged 9 and towns 39 per site.

The UK manufactured prefabs were supplemented by American UK100 prefabs, provided by the US government as part of the Lend-Lease agreement. Initially 30,000 were agreed but after Lend-Lease came to an end in August 1945 the cost went up by over £500 each, the government could not afford it, and only 8,000 were supplied. Local authorities were allocated other prefab types. (3) Read what happened to 8,000 of the rest.

By the end of the war, powers (and the money) to build housing began to shift from local to central government. The Town and Country Planning Act 1947, while handing extensive powers to local authorities for compulsory purchase and planning, reduced and reorganised planning authorities from 1400 to 145. Before the war, local authorities like Stepney had imposed a three storey limit on any new building. By the mid-50s, the government gave extra money to build higher.

Successive post-war housing acts concentrated money in slum clearance. The 1957 act instructed local authorities how to do it and the 1964 act contains a clause specifically relating to the AIROH B2 aluminium bungalows and their demolition (due to corrosion). It may explain why so few examples of the B2 survive.

In 1956 the prefabs were offered to local authorities for £150 each, or to individuals with the proviso that they did not live in them permanently and they would bear the cost of transport and site preparation themselves. Some of the prefabs ended up as holiday homes, or farm buildings. Two ended up as a pub in Norfolk! Many local authorities bought the prefabs and some remain in their ownership to this day. Subsequently some of the remaining prefabs were transferred to social landlords/housing associations and others purchased under Right to Buy legislation.

70 years on, prefabs survive in dwindling numbers. We are often asked why prefabs are not brought back as a solution to today’s housing crisis. To which I reply there is no political will to do it. Local authorities have been hamstrung by successive governments, and as for central government providing public housing that was a one off, never to be repeated. I would be very happy to be proved wrong!

December 2016

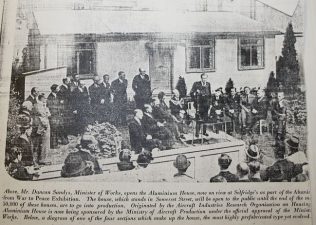

(1) Duncan Sandys MP for Lambeth North 1935-45, Minister of Works 1944-45. HC Deb 07 December 1944 vol 406 cc740-828.

(2) PREFABRICATED HOUSES HC Deb 16 February 1944 vol 397 cc187-8W 187W

(3) Temporary Housing Programme, draft white paper, Ministry of Works 13th October 1945

Comments about this page

[…] and preparing sites in time was not so easy which explains why prefabs are dotted about – the average site was 9 prefabs. Where there was enough space, the layouts were broadly […]

Add a comment about this page